How Would Orwell View Modern Politics?

Probably not they way any of us would expect. The writer had a long history of questioning assumptions and challenging friends and foes alike.

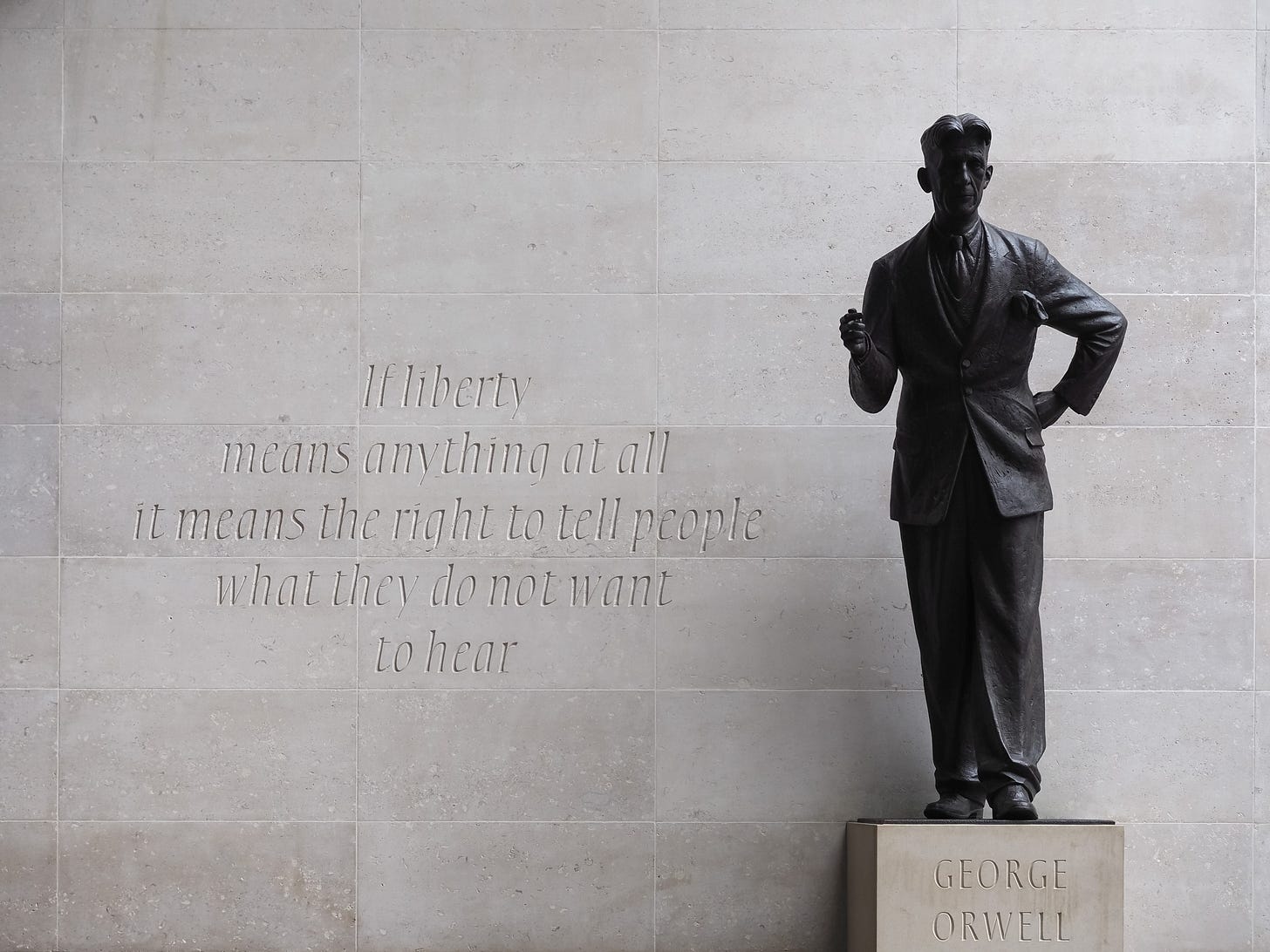

A recent New York Times Magazine article questioned how George Orwell would view our politics. The article points out that Orwell and his most-famous novel, 1984, are frequently invoked by the political right and left in the U.S.

Both sides see the world through Orwellian glasses, it seems.

That may be because the politics that Orwell skewered is of a different time. And Orwell himself is something of a political rarity these days. He was willing to look at the facts and call out leaders he found lacking, regardless of their politics.

Indeed, Orwell may be best-known as a novelist, but to truly understand his thinking on politics and political leaders, you have to read his nonfiction, starting with Homage to Catalonia.

In 1936, Orwell joined his fellow leftists in fighting against the fascist forces of Francisco Franco. He was shot in the neck and almost died, which may have saved his life. While he was recovering in Barcelona, the government forces, backed by the Soviets, turned on the militia that had been supporting them, including Orwell’s unit. Many of his fellow soldiers were imprisoned, accused of secretly supporting Franco.

Orwell left Spain disillusioned. Returning to England, he wrote about his experiences and the betrayal by Spanish government leaders and their backers in Moscow. But he found little support among his fellow leftists. None had been to the front lines to see what Orwell saw; they , who simply didn’t believe what he claimed. He struggled to find a publisher for the book.

As Thomas Ricks points out in this book Churchill & Orwell: The Fight for Freedom, by the late 1930s, democracy had fallen out of favor in much the world. Winston Churchill was a politician on the outs, and Orwell was a lesser-known writer. Both men were skeptical of any government that denied personal freedom, but their views were not mainstream at the time.

“Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written directly, or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it,” Orwell wrote in his 1946 essay “Why I Write.”

Appalled by the 1939 nonaggression pact between the Nazis and the Soviets that led to Germany’s invasion of Poland, Orwell called for England to enter the war against fascism. This, too, angered his leftist buddies. Orwell’s novel Animal Farm was a send up of Soviet Communism. By then, the Soviets had joined forces with the Allies, and he again had a hard time finding anyone to a book that portrayed a key ally as swine.

Over the years, Orwell blasted fascists, totalitarians, communists, socialists and capitalists. He died in 1950, too early to provide his critical insight to the Cold War or modern politics. This also has left him something of a political chameleon, the kind of authoritative voice that either side can twist to its own purposes.

In all likelihood, he would have criticized the imperialization of the American presidency while also taking aim at the left’s efforts to limit speech on social media in the name of quelling “misinformation” or “extremism.”

What set Orwell apart, then and now, was that he formed his views based on his own observations, not simply by what he wanted to believe or what someone else told him.

In his first novel, Burmese Days, he drew from his experiences as a police officer in the British military police to tell the story of imperial bigotry. (He wasn’t above bigotry himself. He referred to the Burmese as “inferior people.”)

He opened an essay about Ghandi by saying: “Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proven innocent,” and went on to question to what extent Ghandi was motivated by vanity. Even so, Orwell concludes that Ghandi was a more effective political leader than many of his time.

And Orwell didn’t leave himself unscathed, either. He acknowledged that part of his motivation as a writer was ego-driven. In “Why I Write,” he added:

All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist or understand.

So what would Orwell make of modern American politics? Probably not what any of us think he would. If he were alive to today, and still running true to form, he would no doubt make keen observations and draw conclusions that would likely anger both sides.

“Good prose is like a window pane,” Orwell wrote. For all our divisions, for all the misinformation spread on social media, for all the ideological posturing of our politicians, it’s that search for clarity, for truth, that should drive us, especially writers.

What would Orwell tell us about today’s politics? The same thing he told us in 1936: Question your assumptions.

Orwell captures the compulsion we writers share and endure. We are "driven on by some demon whom we can neither resist of understand." Some of us, this commenter especially, are prone to talk about nothing but a current project. It's a rabbit hole dammit.

In my imagining of George Orwell visiting us in 2025, he would be exhilarated by the potential of social media in free societies while knowing full well the limitations thereof. Think North Korea.

Presentism can muddy how we regard thinkers of the past. We the opinionated should ask ourselves what we would have done had we been in the situation our subject (in this instance George Orwell) faced when he said the Burmese people were inferior. That's what he saw so is that not truthful? I'm doubtful that we should call "bigotry" from our cultural platform.

It's too easy to imagine that we ourselves would have freed the slaves if we had inherited grandpa's plantation. This is an assumption I enjoy questioning at parties when the virtue signaling gets deeper than the punch bowl.